Agua Segura - Scientific Water Monitoring

Six months transforming a civil service post into a citizen science network: building workflows, training community chemists and making water data public.

Project dossier

- Title: Agua Segura - Scientific Water Monitoring

- Period: November - May 2025 (6 months)

- Location: San Marcos, Guatemala

- Type: Citizen science, digital tools, and community training for clean water in rural San Marcos.

- Partners:

- Caritas Italiana - Servizio Civile Universale

- Pastoral de la Tierra de San Marcos: local community leaders and youth groups

- US-based partner: University & NGOs.

- Pilot network: Three municipalities active, with expansion roadmap toward eleven by 2026.

Role & contributions

Role: Paid volunteer; Project Developer & Strategic Coordinator embedded with Pastoral de la Tierra.

- Tools used: Kobo · Make · Google Sheets · Notion · HTML/CSS · Canva · Hanna multiparameter water quality meter (pH, TDS, EC, temperature).

- Collaborations: Coordinator and staff of Pastoral de la Tierra; five trained community leaders; pilot network of three municipalities.

Key responsibilities

- Designed and co-developed the environmental water monitoring stategy and system with local leaders.

- Facilitated workshops that trained community coordinators in basic water quality and data literacy.

- Digitalised the entire data-collection workflow with Kobo forms, automations and Google Sheets dashboards.

- Created the project website Ojo al Agua and wrote an open-access training course in Spanish.

- Managed communication, visual materials, and digital storytelling for awareness.

Objectives & motivation

Problem to solve

Rural communities relied on untreated river or well water, while municipal monitoring mandated by law rarely happened.

Main objective

Build a participatory water-quality system owned by the communities, using accessible scientific tools and a digital workflow.

Secondary objectives

- Train local leaders to interpret field analyses and act on the results.

- Ensure transparency with public dashboards and open data.

- Promote environmental awareness and self-reliance across municipalities.

Personal drive

Transform a civil service placement into a real Project Catalyst experiment that merged chemistry, digital tools and human impact to make knowledge actionable.

Approach

Citizen science + agile implementation

- Context analysis: mapped community needs and existing water governance.

- Co-design: defined monitoring protocols with partners to balance rigor and cultural practices.

- Prototype & test: piloted the workflow with one municipality before scaling.

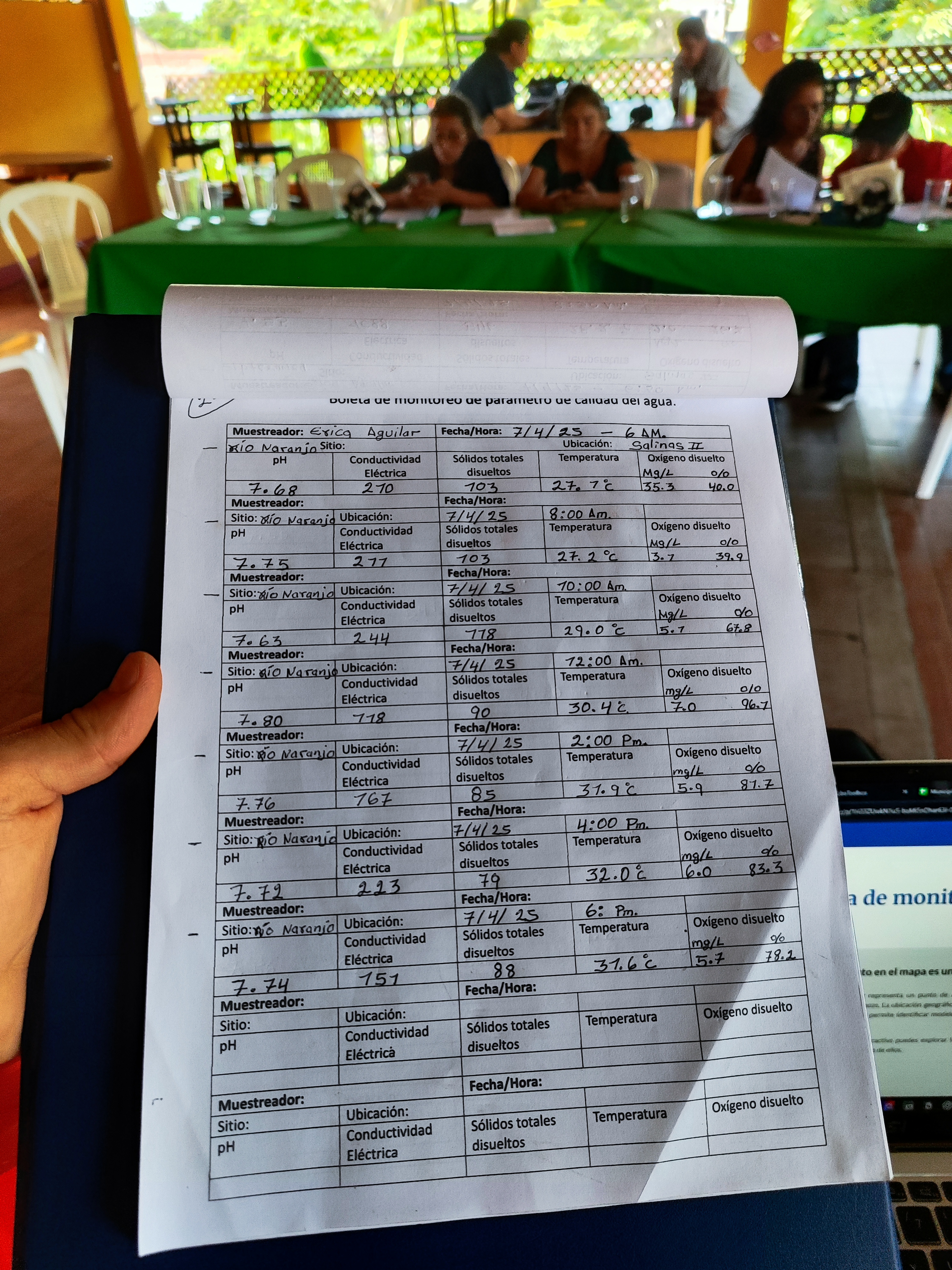

- Digital backbone: transitioned from paper logs to Kobo forms, automations and live dashboards.

- Capacity building: authored an eight-module online course and facilitated experiential workshops.

- Communication: launched the Ojo al Agua public site and storytelling materials.

Key challenges

- Bridging cultural and linguistic barriers through practice-first workshops.

- Working with limited condition, tools, digital infrastructure and connectivity.

- Designing a system that could scale while remaining low-maintenance and low-cost.

- Writing and preparing material and SOP to continue allow anyone to run everything.

Key results

- Launched the first citizen-science water monitoring network in San Marcos.

- Fifteen-plus citizens trained to collect, interpret and report basic data across three municipalities.

- Centralised database and dashboards accessible online for transparency and advocacy.

Deliverables

- 🧾 Calidad del Agua - eight-module Spanish training course for community monitors.

- 🌐 Ojo al Agua public site: maps, dashboards and community resources.

- 📊 First report: made the first report about the project with data and situation overview

- 🎥 Visual storytelling: photo and video materials documenting fieldwork.

Impact & learnings

The system continues to run after handover, with partners expanding the network toward eleven municipalities and using data to advocate for safe water.

- Designing for continuity matters more than delivering a one-off intervention.

- Simple tools become transformative when wrapped in trust and training.

- Project Catalyst principle confirmed: enter a system, understand its rhythm, leave it stronger.

Field story

From zero to a shared vision

When I arrived in the highlands of San Marcos, Guatemala, I carried little more than my personal stuff, a few ideas, and six months to make them work. Officially, I was there as a Civil Service volunteer with Caritas Italiana, supporting the local partner Pastoral de la Tierra. In practice, I was trying to answer a question that has followed me for years: how can science serve people directly, without losing its precision?

The first weeks I was mostly listening. The partner organisation was strong in social action but had never run an environmental monitoring project. They dreamed of one but lacked a clear path. Together we decided to focus on what mattered most to the communities: water. Many families still rely on rivers and wells that are rarely, if ever, tested. Although Guatemalan law requires municipalities to monitor water quality, few actually do.

The idea took shape as a citizen-science project that could outlive my presence. Instead of only collecting samples myself, I would build a system the communities could own. It needed to be simple, transparent, and teachable. We called it Agua Segura.

The plan unfolded in three layers:

- Training and empowerment – form community leaders who could run the tests.

- Data collection – start with one municipality, then expand to others.

- Digitalization – replace the fragile paper process with an automated one.

Armed with a portable combo measurer field system, I spent the first month introducing the basics: what pH means, why conductivity matters, and how contamination travels through soil and crops. We met under tin roofs, beside rivers, sometimes with kids playing around while we discussed acids and bases. The language barrier was real, my Spanish at time was somewhere around a B1 but non verbal communication skill bridged the gap.

By the second month, it was clear the paper system would collapse under its own weight. Community members sent handwritten tables via WhatsApp; one staff member typed them into a messy Excel sheet. The process was slow, error-prone, and unsustainable.

So I designed a digital workflow from the tools I had. Using Kobo Toolbox, I created mobile forms that automatically uploaded data to the cloud. From there, an online automations cleaned and synced the information into Google Sheets and a simple online dashboard. It took me a while to figure it out but in few weeks, we had a real-time system accessible to anyone with a phone.

To make the data public, I built Ojo al Agua, a minimal website on Google Sites. It displayed maps, results, and resources in Spanish, a transparent mirror for both citizens and local authorities.

Technology alone was not enough. Knowledge had to be passed on. I wrote an eight-chapter online course in Spanish, explaining everything from the chemistry of water to interpreting field results and reporting hazards. The text was reviewed by local staff and later published openly on the website. It became the foundation for new leaders joining the program.

By the end of the project, more than 15 citizens across three municipalities were actively monitoring their water. The goal for the following year: eleven municipalities. I left behind not a closed project, but an expanding network.

The project delivered tangible results but more subtly, Agua Segura shifted the local perception of science. It showed that science and rural community action can coexist, that evidence, when shared, is power.

I left Guatemala with more than field data and experience. I learned that designing impact means building systems that survive you. Simplicity is not a weakness; it’s one way innovation travels in places with limited resources.

The project taught me how to merge the precision of science with the empathy of storytelling, a combination that has become central to my identity as a Project Catalyst.

The Catalyst spirit

Agua Segura began as a fallback after a failed start in another country. It ended as a prototype for how I want to work in the world: blending chemistry, data, and human collaboration to create visible, lasting impact. The communities of San Marcos continue to collect samples, upload data, and advocate for cleaner rivers. Their results an stories still reach me in another country. Each datapoint or photos is a reminder that transformation starts with attention.

In the end, I didn’t just monitor water quality, I helped monitor hope.

Gallery